Written by

on

I recently attended a conference with an excellent keynote by Dr. Nathan Grawe, a professor of economics at Carleton College and author of “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education.”

As the title suggests, Grawe explores how the changing demographics of the United States will impact demand for higher education in regard to the number of students going to college, the makeup of those students, and the types of institutions they’ll choose. (Note: I have not yet read Grawe’s book, but at the time of this writing, it’s currently being shipped, and I’m looking forward to reading it!)

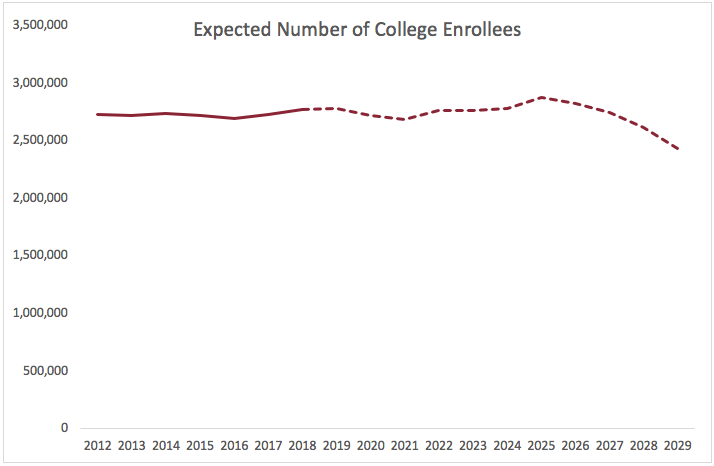

The findings will make a lot of higher ed professionals nervous. And, for some, rightly so: The total number of traditional-aged students enrolling in college is expected to decline in the coming years with more dramatic declines occurring in the late 2020s.

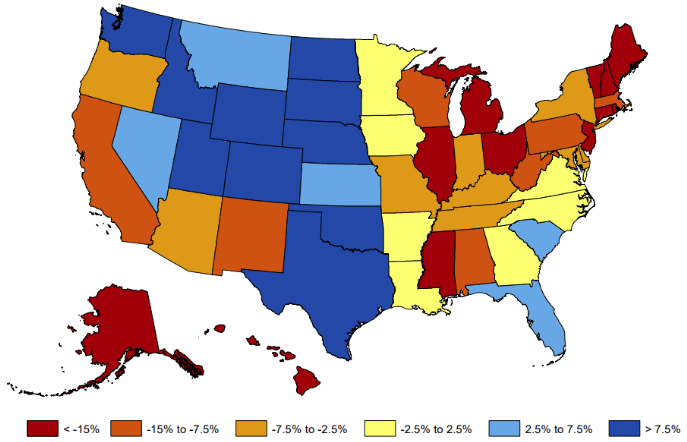

As we know, however, these changes aren’t equal across all states or regions. Some areas will grow, others will decline. New England and parts of the Great Lakes will face the steepest declines in high school graduates, while parts of the South, Plains, and Rocky Mountain areas will grow. The map below from Grawe’s research shows the forecasted growth in high school graduates between 2012 and 2032 by state.

Of course, the research is fascinating (if a bit unnerving), but I’m more interested in how these demographic changes affect how higher education is delivered. In other words, if we know that changes are coming, how will higher education adapt in response?

The list below includes five things I believe will change as a result of shifting demographics in our country. Some of these come from Grawe and some from my own thoughts and experiences. This list is hardly comprehensive, but it reflects some of the ways in which higher ed marketing, enrollment management, and administration may change in response to an evolving “customer base.”

#1. Redefining first-generation college students

In the past, the definition of a first-generation student has been straightforward: People who would be the first in their families to attend college (i.e., neither parent has a college degree). The assumption is that first-generation students need more guidance to navigate college. Parents who went to college can help their kids understand what to expect, but first-generation students are figuring it out for themselves.

This will continue to be an important audience for colleges to serve in the future, but our understanding of a first-generation student may change. We’re in an age when, for the first time, a student’s parent may have a bachelor’s degree but never set foot on a college campus. Parents who earned a degree online can help their kids navigate the world of majors vs. minors and how to use a college’s online library, but they’ll be less helpful when it comes to figuring out residence hall issues, how to get involved in extracurriculars, and when to speak with an advisor. Colleges will need to consider how to serve this segment of students who are not technically first-generation but nevertheless need guidance on the college experience.

#2. Assessing (and promoting) academic strength

Grawe anticipates the college student population will continue to diversify. Latinx students will make up a greater share of the college-going population, as will students of minority races/ethnicities often categorized as “Other.”

Historically, non-white and non-Asian students have scored lower on standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT, which colleges frequently use not only as indicators of a student’s preparation for college, but also as promotional tools to demonstrate the academic strength of the incoming class. If the prospective student pool diversifies, will colleges continue to use these standardized tests in the same way? What other metrics may be better indicators of a student’s preparation? Will average scores decline and, if so, will colleges continue to use them as a marker of academic strength?

#3. Continued pressure on tenure

In the wake of the recession in the late 2000s, budgets were tightened, and colleges and universities sought to limit expenses by hiring adjunct professors as opposed to full-time faculty. Rather than a temporary fix, however, it appears this practice has become the new normal. Newly minted PhDs have a hard time finding full-time employment in academia and instead cobble together adjunct appointments at multiple schools, conduct post-doc research, or find work outside of the academy.

If declining numbers of high school graduates put a strain on enrollment, universities will struggle to sustain current business models. For a long time, tenure has been a standard practice at colleges and universities that seek to attract top talent. But if tenure is a fixed cost in an era of turbulent revenues, some colleges will be forced to re-evaluate tenure’s benefits vs. its costs.

#4. Increased focus on international enrollment

When the domestic pool becomes smaller, schools will look elsewhere to maintain enrollment. International students offer schools an opportunity to supplement enrollment when domestic students are not enough. However, it’s not as easy as merely opening the doors to more students. We know that recruiting international students requires a lot of time and money to be done well—an investment that some schools have not been willing to make (yet).

Additionally, it’s impossible to say how American protectionism may discourage international students from coming to the United States in the future (or whether that will change after 2020). However, it remains true that international students view U.S. colleges and universities as an outstanding option for international study. Therefore, it’s safe to expect an increase in international students in the future.

#5. Increased focus on retention

When it becomes more challenging to recruit new students, schools will strengthen their efforts to keep the students they already have. In other words, I expect we’ll see a greater focus on retention efforts so colleges sustain overall enrollment even while new student recruitment may decline.

One final thought on how changing demographics will bring about new priorities and processes: As mentioned above, New England is expected to face the steepest declines in new high school graduates. This will create a competitive environment in which enrollment growth depends on brand strength, recruiting in other parts of the country, and/or innovating to deliver a college education in new and better ways. Innovation may come in the form of new academic programs or new methods of delivery. Grawe predicts New England colleges that grow in the coming decades will provide illustrative examples of how to deliver postsecondary education in a changing environment. They will serve as case studies for other institutions around the country seeking to find success in a shifting landscape.

Again, I present this as a list of thoughts and reflections—not as a definitive set of “will-be’s,” but rather as a short list of “could-be’s.” The history of higher education shows that schools have been responsive to changes in the student population. For example, consider the growth of professional programs that resulted from the end of World War II and the signing of the GI Bill. We can expect that higher education will continue to evolve as the student population changes. It’s only natural that a business responds to the needs of its customers since doing so ensures its survival. The same can be expected of our nation’s colleges and universities.

Ready to Get Started?

Reach out to us to talk about your strategy and goals.